Lending Club Credit Model

A classic data science application forms the center of this Dataquest exercise that comes in the machine learning section. The use case is the decision to lend. Or more precisely to predict whether a customer will default on the loan.

A classic data science application forms the center of this Dataquest exercise that comes in the machine learning section. The use case is the decision to lend. Or more precisely to predict whether a customer will default on the loan.

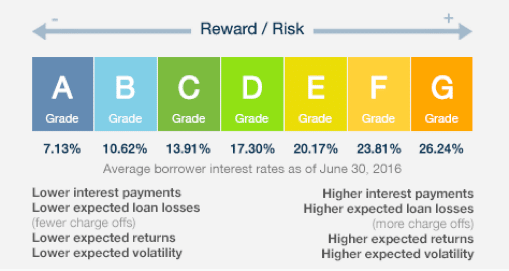

The data comes from Lending Club. The company, founded in 2006 really pioneered peer to peer lending in the US. The idea is that if you have some money to invest you can go on their website and directly lend it to someone who wants to borrow. Hence peer to peer instead of going through the bank as an intermediary. It ultimately had a IPO in 2014 worth nearly a billion dollars. The company has had some bruises and bumps since then, but as of this writing in March 2018, it retains its unicorn status with a market cap over $1.3bn.

Lending Club makes it’s loan data available on its website, and the data used in this exercise is from 2007 to 2011. The data dictionary is also there on that website.

I liked this exercise because it provided an opportunity to apply a number of core skills common in data science projects:

- data cleaning and preparation

- data exploration

- feature selection and engineering

- choosing an appropriate target variable

- defining an error metric

- applying an algorithm for prediction (logistic regression, random forest)

- handling the problem of class imbalance (higher penalty for the few defaults amidst lots of well performing loans)

- and drawing business conclusions from the analysis

To predict default, I used several variables like the loan amount, interest rate, installment amount, and term of the loan, length of employment, annual income, home ownership, loan purpose and so on. Between the logistic regression model and the decision tree, the combination of the later in a random forest model had the best performance. This Python Notebook has the details of the analysis.

In the end though, I couldn’t get a model that would really cut it in the real world. The most conservative model would have a 2.5% default rate but would turn away 93% of applicants and require a break even interest rate of 2.6%. This is probably too conservative. A model that would approve 20 percent of applications would have a 7% default rate and require a 8% interest rate to break even. This is a default rate that is probably too high. More work to be done here before this model is ready for production.